Excerpt from an article “Rethinking the role of the strategist. Strategic planning has been under assault for years. But good strategy is more important than ever. What does that mean for the strategist?”, McKinsey Quarterly, November 2014, by Michael Birshan, Emma Gibbs, and Kurt Strovink.

Many companies have an executive to guide their strategies. The discipline’s professionalization, which began in earnest in the 1980s as it evolved from the chief executive’s domain into a core corporate function, prompted the creation of heads of strategy, strategic-planning directors, and, more recently, chief strategy officers (CSOs). Who better than a professional strategist to help meet the big new uncertainties of the 21st century?

Yet today’s unpredictable environment is utterly incompatible with what, historically, has been one of the chief responsibilities of many strategists: leading the annual strategic-planning process. While nothing new, the weaknesses of traditional strategic planning—characterized by a lockstep march toward a series of deliverables and review meetings according to a rigid annual calendar—have been amplified by the importance of agility in a rapidly changing world.

Strategists have responded by increasing the scope and complexity of their roles beyond planning. In a recent survey of nearly 350 senior strategists representing 25 industries from all parts of the globe, we found an extraordinary diversity of responsibilities (13 by our count). But running the planning process still loomed large, ranking second in priority on that list, even if many respondents said they would prefer to spend significantly less time on this part of their role.

There’s a way out of this box for chief strategists and other senior leaders, particularly CEOs, CFOs, and board members, whose roles are deeply intertwined with the formulation of strategy. The starting point should be thinking differently about what it means to develop great strategy: less time running the planning process and more time engaging broader groups inside and outside the company, going beyond templates and calendars, and mirroring the dynamism of the external environment.

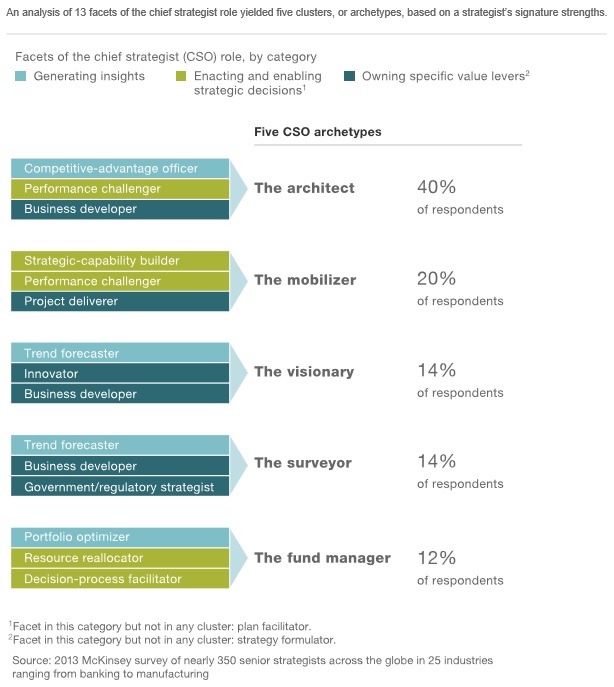

But this isn’t enough. Achieving real impact today requires strategists to stretch beyond strategic planning to develop at least one of a few signature strengths. Several important facets of the strategist’s role emerged from our research, including reallocating corporate resources, building strategic capabilities at key places in the organization, identifying business-development opportunities, and generating proprietary insights on the basis of external forces at work and long-term market trends. A number of these roles are more appropriate for some strategists and organizations than for others. But the core notion of stretching and choosing is relevant for all.

Developing signature strengths

Four years ago, executives around the world told us their companies were creating, by their own admission, substandard strategies. Only 35 percent were generating strategies that passed more than three of ten tests we use for measuring the likelihood that a given strategy would beat the market. And many respondents blamed the ineffectiveness of the annual strategic-planning processes for the state of their companies’ strategies.

Since then we’ve sensed, in our work with a wide range of global organizations and strategists, a growing recognition that traditional strategic-planning processes are insufficient to absorb the shocks and disruptions characterizing their markets and to stimulate the ongoing deliberation that a top-management team requires. Increasingly, they recognize a need to rethink their approach to strategic planning and to embrace a more frequent strategic dialogue involving a focused group of senior executives. Effective organizations seem to be transforming strategy development into an ongoing process of ad hoc, topic-specific leadership conversations and budget-reallocation meetings conducted periodically throughout the year. Some organizations have even instituted a more broadly democratic process that pulls in company-wide participation through social-technology and game-based strategy development.

Our research supports one of our major observations about what it takes to innovate in the development and delivery of strategy: over and over, we’ve seen that the chief strategists best at driving more dynamic approaches have a professional credibility that extends well beyond a traditional process-facilitation role. At the same time, we’ve seen tremendous diversity in the characteristics of effective strategists. In a quest for greater precision, we applied statistical cluster analysis to the 13 facets that chief strategists responding to our survey described as most important to their efforts. The analysis yielded five clusters in which the strategist’s role becomes more than the sum of its parts. Widespread across industries, these clusters embody choices that face every strategy leader.

For reading more click here.

Leave A Comment